The stars who open a doorway to the past

[ad_1]

The end of each year comes with many rituals.

There’s the “Word of the Year”, “Newsmaker of the Year”, “Books of the Year”.

And then there is the annual “People we lost this year” list.

2023 has seen its fair share of loss in the world of culture. Tina Turner. Matthew Perry. Ryan O’Neal. Gina Lollobrigida. Burt Bacharach. Raquel Welch. Harry Belafonte. Milan Kundera. Sinead O’Connor. Bishan Singh Bedi. Vani Jairam. Gitanjali Aiyar. Sumitra Sen. Gufi Paintal. Anup Ghoshal. And that is to name just a few.

Some of those deaths make front page news. Some are names I have never heard. There are always a few I thought had died years ago. But the ones that cause a real pang are those I had not thought about in years but at one time meant so much to me. Those losses feel truly poignant, as if opening a hidden doorway to a time I had long forgotten.

They bring back memories not just of a song or a book but everything that had happened around them—a secret crush, the loss of a pet, an ice-cream sundae, the first cigarette or the first swig of Old Monk with coke. It’s a reminder of a person we had once been, someone we had long forgotten about, someone we have outgrown, someone who thought reading Ayn Rand and Jonathan Livingstone Seagull was the height of rebellious cool and learned about sex in dog-eared hand-me-down copies of Harold Robbins and Jackie Collins.

Tina Turner was the first rock star whose poster I had pinned to my cupboard in my bedroom. I remember it clearly, that short black dress, the boots, the shag hair. Gitanjali Aiyar reading the nightly news was a masterclass in diction and delivery. Harry Belafonte’s Jamaica Farewell was in my DNA as were Anup Ghoshal’s joyous songs from Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Bayen films. We hummed those songs, watched those actors on screen, read those books and at some point left them behind—the debris of childhood and adolescence.

Only in death do they return to the foreground again—the ghosts of decades past. I suddenly have a flashback of going to Bijoli cinema in Kolkata with my family and excitedly watching that Ray film on the big screen, and as Anup Ghoshal started singing Eshe hirak deshey, I knew that when I came out, I would buy that cassette. That movie theatre is still there, somehow clinging on when most other single cinema halls have been demolished, but I have not been inside for decades.

Now after years I can suddenly hear a strain of Vani Jairam singing Bole re papihara. I can clearly see the paperback cover of Erich Segal’s Love Story (made famous on screen by Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw), always available in some secondhand book stall on the street. I can recall Gufi Paintal adding a machiavellian touch to my Sunday mornings as Shakuni in TV series Mahabharat. And nothing compares to Sinead O’Connor, though at one time I felt I could not bear to listen to that song one more time. It was all over the airwaves and coming out of my ears.

We call them cultural icons in death. In their lifetime they were just part of the cultural zeitgeist. Some like Tina Turner and Harry Belafonte had storied careers. They were bona-fide legends. Some disappeared from our world after one song, one book, one role that made them household names briefly. Yet for a moment we had all basked in their star shine.

To be a cultural icon is different now. Social media has broken pop culture into many shards. The superstars of one niche are virtually unknown in another. No Gitanjali Aiyar or Salma Sultan can be the “voice” of the nation because that old Doordarshan monopoly is long gone.

Anup Ghoshal was never one of the most famous singers in India or even Bengal but generations of Bengali children can still hum those tunes from Goopy Gyne. Those songs had instant recall. It’s doubtful that can happen anymore not because there will not be new singers but because our attention is far too fragmented for one song, one singer, one newscaster to capture us in that kind of cultural thrall.

Once, we assumed that the cultural torch just passed from generation to generation—a Raj Kapoor giving way to a Rajesh Khanna giving way to an Amitabh Bachchan on to a Shah Rukh Khan. But that’s not true anymore. There are always new stars but few superstars who can forge that one ring to rule us all and in the darkness bind us.

Social media gives us “stars” who are everywhere and then nowhere at all—Orry, the BFF of Bollywood star kids, Jasmeen “Just like a Wow” Kaur or Ranu Mondal aka the “Lata Mangeshkar of Ranaghat”. In a few years we will forget about them as well but for a moment they too rule the internet or at least a slice of it. They are not necessarily icons but they are certainly hashtags. And in a world that seems to value going viral over all else, sometimes being a hashtag for a blink of an eye is fame enough.

This is not an old guy’s lament for the good old days when the stars shone brighter. It is just that the quality of stardom itself has changed.

It is a fact that cultural icons are not just about raw talent. They somehow hit the right note at a formative moment of our lives. That is what makes them iconic. Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and Amitabh Bachchan captured the political mood of an entire generation.

Over time I found myself less interested in the Top 10 lists. The names that appear on Grammy nominations are more and more unknown to me. I am less invested in who won and who did not. That’s not to say they are lesser singers. It’s just that as we grow older and more set in our ways, we create fewer new cultural icons, preferring the comfort of the nostalgia of the ones who had accompanied our early years.

Time magazine just anointed Taylor Swift as the person of this year. She is a record-breaking superstar, but I have to admit that every time Swift or one of her songs comes up in a crossword, I draw a blank. I am clearly not a Swiftie by any means. It’s more a reflection on me than on her. Her fandom is unparalleled, but I can only admire it from outside.

At one time these icons provided the soundtrack for the way we wanted to imagine ourselves. They represented what was exciting about the world outside, one that we were determined to explore and conquer. They were portals into that world and signposts. But as we age, we don’t need those signposts as much. It is not that the new cultural icons do not speak to me, but rather that it is I who do not hear them.

That is why each time I read the “People we lost this year” list, I feel my world shrinking. The people who shaped my world are leaving and I realise I cannot just replace them with new ones easily.

I mourn not the person who died, but the person I was when they had helped me reimagine my world.

It’s a cliche to say the person leaves but the work lives on. The person also mattered. Their presence reminded us of a time when we too felt we were made of stardust, rife with possibility. They shaped us, and at the same time in a way bore witness to the persons we became.

As they exit the stage, we realise a small part of ourselves has become untethered as well—a tape that unspools into the night, magnetic with the memory of the way we once were.

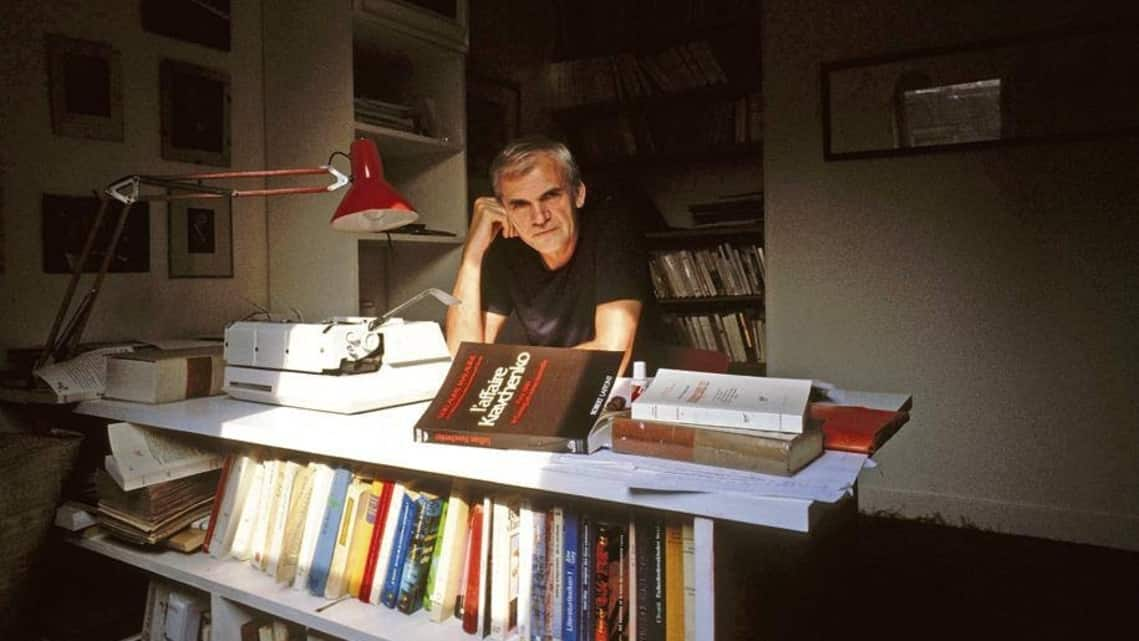

Cult Friction is a fortnightly column on issues we keep rubbing up against. Sandip Roy is a writer, journalist and radio host. He posts @sandipr

[ad_2]

Source link